How I Do It: One-Part Silicone Rubber Cut Molds

This article is the first in what I hope will be a series that details each part of my toy making process, starting with how I make the most common type of silicone rubber mold that I use to duplicate either parts of or an entire figure: the one-part mold (also known as a “cut” mold). If time allows, I’ll eventually roll out more How I Do It articles about other types of molds, everything I know about resin casting, painting, customizing/oversculpting on existing parts, and anything else that springs to mind. But for now, I want to focus on cut molds.

I’ll start by first listing my equipment and materials

before getting into what a one-part cut mold is, what it is not, and why I

prefer them to two-part molds.

My Equipment and Materials:

- Ablaze 1.5 Gallon Vacuum Chamber and Pump Kit

- Note that the placement of pressure regulator on my is not in the same position as the kit you can currently buy on Amazon. I don’t know why this is, but the steps for using it remain the same.

- Specialty Resin and Chemical Cast-A-Mold 25 (Specialty Resin and Chemical Silicone Thinner is optional but recommended)

- Digital scale

- Super glue and super glue accelerant

- Toothpicks and/or barbeque skewers

- Hot glue or silicone sealant

- Sulfur-free non-hardening modeling clay (Sargent Art Plastilina Modeling Clay is what I use)

- Plastic cups and/or Lego baseplate and Lego bricks

- Dowel rod (the largest one in your typical package of dowel rods)

- X-Acto blade (or generic hobby knives will do)

- Safety Equipment/PPE:

- Disposable plastic gloves

- 3M half face piece respirator mask with general-purpose respirator cartridges 6006

Note that this is not a definitive list. You can use

whatever brand of silicone or type of vacuum chamber and vacuum pump that you

want, just be sure to thoroughly read the labels and the instructions for both

your silicone and your vacuum chamber equipment as they will almost certainly

differ from what I write about here. I cannot stress that enough.

What A One-Part Cut

Mold Is/Is Not

A one part cut mold is exactly what the name would suggest: it’s a mold, it’s only one part, and you have to cut it open. An open-face mold is also a one part mold (also called a push mold). But unlike a cut mold, it typically only encompasses one side of a part that is either pressed into the mold material or the mold material is poured over the one side (typically the most detailed side of the part). Here’s a quick open-face mold that I made not with silicone, but with ImPressive Putty from Composimold. I’ll go more into that if I ever do a separate article on open-face/press molds, but there’s really not a lot to these.

Another thing a one-part cut mold is not: a two-part mold (also known as a clay-up mold). As the name would suggest, two-part molds differ from cut molds because they not only consist of two parts (a front side and a back side), but each of these parts is molded in two layers. Again, I’ll go more into detail on what two-part clay-up molds are when I eventually get around to making an article on those but know that I typically avoid two-part molds where I can because most of my previous efforts have resulted in castings with terrible mold lines that are difficult (and often impossible) to fully clean up. One part cut molds help you avoid this, since (if done right) the mold-lines are considerably less severe. But here are some of my more recent examples of two-part molds that I made.

I typically only employ two-part molds on relatively thin, flat pieces that would waste a lot of silicone if I attempted to do them as a one-part mold due to all the excess space around the part. With two-part molds, you have slightly more control of how much space you can allocate in your mold, so that is one advantage to using them (unless of course, you custom build a mold box that is specifically tailored for every cut mold like Robert Tolone does on youtube, but I don’t go quite that in-depth with it).

Creating A One-Part Cut Mold

The process of creating a cut mold can be boiled down to the following:

- Glue air vents and a pour spout (funnel) to the part you want to mold. This part is called the “master”.

- Secure the master in a mold box or mold surround and secure the mold surround against any potential leaks.

- Determine the amount of silicone needed to create the mold.

- Mix the silicone rubber.

- Pour the silicone into the mold surround until the master is fully enveloped in silicone with some extra on top (preferably about 1/4" or more).

- Wait for the silicone to cure.

- Cut the mold just enough to remove the master.

- Seal the cut mold with rubber bands and/or packaging tape.

But let’s start at the beginning, shall we? Here are the

master parts that will serve as the examples for the bulk of this article. It’s

a pair of legs and a torso from a 1980’s pirate figure. I’ll be walking you

through how I made a cut mold for each of these parts.

The first thing I always do when I start the process of

molding something is to determine the “problem areas” where air bubbles are

likely to get trapped or places where the resin will have a difficult time

reaching. To mitigate these problem areas, air vents (or sprues) must be added.

Picture this: as resin is being poured or injected into a mold, it fills the

mold (or more accurately, the cavity inside the mold) from the bottom and

pushes the air up. As the air is being pushed up, it needs a path to escape

from the mold so that it’s not trapped in there as air bubbles (which, in turn,

will prevent the mold from filling up all the way). That’s where air vents come

into play.

What I typically do is superglue a tiny funnel to the “entry

point” where I pour or inject the resin. All of the funnels I use now are

either ones I’ve saved from previous resin castings or ones I quickly made out

of polymer clay. Just make sure the funnel has a large enough “mouth” to allow

the resin to easily pour into the mold. For the air vents, I cut pieces of

skewer or toothpick to length, superglue those in place, and spritz them with a

super glue accelerator. In this case, I glued the air vents to both sides of

the hips for the legs and both of the ball joints for the torso.

These will be upside down when they go into their respective

mold boxes since the funnels and vents are what will be affixed to the bottom

of said mold boxes. When the mold is complete, they’ll be right-side up. It’ll

make sense as we continue on, I promise.

For venting more complex master parts, like action figure

arms for example, you would vent it by doing something like this:

I did the mold boxes for these parts in two different ways.

For the legs, I did the traditional method of just gluing it to the bottom of a

plastic cup. As you can see, the air vents don’t quite reach the bottom of the

cup like the funnel does but that’s something you can fix in post. After the

mold is cured, I came in with a hobby knife and extended the air vent

channels by carving out the silicone until they reached the surface and gave the air adequate room to vent.

Remember, the one trick to air vents is that they have to

extend all the way to the surface. Otherwise, they’re not venting anything.

For the torso, I wanted to conserve as much silicone as

possible, so I built a mold box out of Lego bricks after affixing the master to

the Lego baseplate using sulfur-free non-hardening modeling clay. Once the

master was secure in the mold box, I reinforced the sides with packaging tape

and shored up the bottom with the same non-hardening modeling clay to prevent

any leaks. Lego bricks are usually pretty tight, but mine have been through

hell and back and are somewhat loose, so I don’t take any chances.

To further conserve silicone, I filled up the bottom with

tiny chunks of previous silicone molds that were either failures or ones I’ve

retired. I did this for the torso mold in the cup too, I just didn’t take a

picture of it. Whenever I have a would-be mold with a considerable gap between

where the funnel and air vents meet the “floor” and where the master part

proper begins, I will always fill it up with “recycled” silicone.

Just make sure that the silicone chunks are made of the

exact same type of silicone that you’ll be using to pour the mold, otherwise

the silicones won’t “merge” with one another and the entire thing will be

ruined. I buy my silicone in bulk from the same place, so it’s all the same type

and I don’t have to worry about that. But if you got some Smooth-On brand

silicone rubber and you’re thinking of adding chunks to it that were made from

Let’s Resin brand silicone…you maybe want to stop and think about that for a

second. Even if both brands of silicone are tin-cured or platinum-cured,

there’s still a chance that they won’t stick to each other, so you’ll want to

be aware of that and not take any chances.

But what if you don’t have any Lego and there’s a part that

won’t fit in a plastic cup? Well, you could do a number of things, but the most

expedient method for me is to affix the master by its funnel and vents to an

acrylic sheet using either hot glue or silicone sealant (like the Loctite stuff

you find in the plumbing section of a hardware store or the automotive section

of Dollar General). The acrylic sheets that I use come in packs on Amazon and

are the ones typically used for picture frames. Just buy the cheapest ones.

They’re reusable until they break.

If you’re using a new acrylic sheet, don’t tear off the

protective plastic or paper covering before you glue the master and cup onto

it. Once the silicone is cured, you’ll be able to peel the protective covering

off, mold and all. It should save you a little bit of cleanup.

Once the master is in place, take a plastic cup, flip it

upside down, cut out the bottom (which is now the top), and place a bead of hot

glue or silicone sealant around the bottom edge of the cup before placing it

over the master. Then reinforce the bottom of the cup with more hot glue or

silicone sealant and wait for it to cure. If you use hot glue, you’re going to

want to reinforce the bottom with non-hardening modeling clay like what was

previously done with the Lego mold box because hot glue isn’t particularly strong

and it almost always leaves gaps. That’s a big reason why I don’t like hot

glue, though it does cure considerably faster than silicone sealant. But in the

example below, I used silicone sealant to secure both the cup and the master.

.jpg)

Now comes the part where you actually break out the

silicone. But first, determine how much silicone you’ll need to make the mold.

Alumilite has a really useful volume calculator on their website (and watch

their video on their calculator too). While it isn’t 100% accurate all of the

time, it will get you a decent ballpark range. I always round the number up so

that I have a little bit of silicone left over and if it’s too much for the

mold box, I usually have a smaller, “dump” mold set up on the side to catch any

excess silicone rather than letting it go to waste. It’s usually something like

a miniature figure or an action figure head. Since I use the same silicone for

everything, I can always top up my dump mold later and not worry about whether or not the silicone will stick to itself across multiple pours.

Once you determine the amount of silicone needed, place your

mixing container on your digital scale and press the “tare” button to zero out

the weight of the container. Now, the scale will only be measuring the silicone that you pour into the container independent of the weight of said container. If your silicone is measured by volume, you can

skip all this stuff about measuring by weight since it probably won’t apply to

you. Instead, just pour the required amount of Part A into a measuring cup

(ideally a disposable one), pour Part B into another measuring cup, then

combine the two by either pouring them into a third measuring cup or pouring

one of the parts into the other’s cup. Either way, the final container should

be large enough to not only contain both parts, but leave plenty of room in

said container for the vacuum degassing to come. The container should only be

about half full after both Part A and Part B of the silicone is added, two-thirds

full at the most. You’ll see why in a bit.

At this point, you should probably be aware of your

silicone’s mixture ratio as well as if it’s measured by weight or volume. The

Cast-A-Mold 25T silicone goes by weight and it’s a 10:1 mix ratio. So if 100

grams of silicone is required (like in the example pictures below), you’ll pour

10g of Part A first and pour 90g of Part B second. Due to the high viscosity of

Cast-A-Mold 25T (30,000 cps if that means anything to you), I always add a

little bit of silicone thinner after the desired weight is reached to improve

the flow of the material. Usually about 5 to 10g of silicone thinner depending

on the size of the batch.

Then I mix the silicone using a wooden dowel rod until both

parts are fully blended and there are no more streaks in the silicone. Use the

biggest, thickest dowel rod you can find. These work especially well in

scraping the sides and bottom of the container to ensure an even mix.

I mix until my silicone assumes that uniform green color, but

other silicones will advise you to mix the two parts for a set number of

minutes. If that’s the case, then just do that. Don’t try to cowboy it, it

never hurts to follow the manufacturer’s directions on the box or labels.

Then, place your container in your vacuum chamber. I like to

line the bottom of my chamber with wax paper. Make sure the vacuum pump is

plugged in and its exhaust cap is removed.

Place the lid on the vacuum chamber and make sure that it’s

centered and not askew. Now take note of the positions of the red and blue ball

valves on the vacuum chamber. For this particular chamber, this direction means

that both the inlet to the vacuum pump (red) and the outlet (blue) are in the

CLOSED position.

Turn on the vacuum pump and set the red inlet valve to the

OPEN position (pictured below) to allow the pump to start introducing vacuum

into the chamber. Keep a close eye on the gauge. You’ll want the vacuum to be

between 25 and 30 Hg. Once this level of vacuum is reached, return the red

inlet valve to the CLOSED position. You can now turn off power to the pump, as

vacuum will be maintained for as long as both ball valves remain closed.

If you’re wondering why you should mix your silicone in a

container that is considerably larger than the amount of silicone needed, it’s

because the silicone will expand and bubble up like a witch’s cauldron when

it’s being vacuum degassed. If you use too small of a container, the silicone

will bubble up and over the top and spill out over the sides and create a huge

mess.

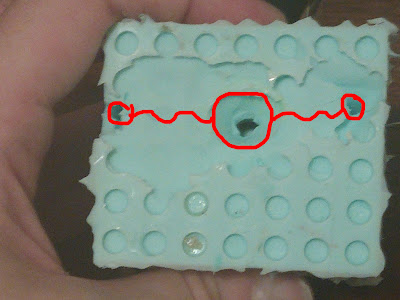

Here’s a pic I took of some silicone in the process of

degassing. Granted, this isn’t at the peak of its expansion but you can tell

from the film left behind on the sides of the container just how much it

bubbled up before collapsing back down. Without vacuum degassing, all those air

bubbles would end up in your mold. That’s a problem because when you’re

pressure casting, all those air bubbles trapped in your mold get popped,

leaving tiny voids in the mold for the resin to flow into. That, in turn, leaves

your final casting covered in little spikes and pimples and you with a useless

mold.

Even if you don’t use a pressure pot to cast your resin

(though you really should), you should still eliminate air bubbles in your

silicone with a vacuum chamber because again, take a look at that picture of

all the bubbles being degassed from the silicone. If these bubbles aren’t

eliminated, they’ll end up in your mold and leave it looking like Swiss cheese

(especially if your silicone is in the high viscosity range of 20,000-30,000+

cps). I know a lot of the silicone mold rubber kits you find on Amazon claim to

be “self-degassing” on the box, and while that’s true to a point, you're going to need a vacuum chamber if you're also going to be using a pressure pot and you'll need a pressure pot if you're casting resin. So, in a roundabout way, you need a vacuum chamber.

Depending on the size of the batch, I typically let my

silicone degass for anywhere between 20 to 30 minutes. Cast-A-Mold 25T has a

working time of one hour and it only takes me a few minutes to actually pour it

into a mold, so I make sure to give it all the time it needs to eliminate all

the air bubbles. For fast curing silicones, you won’t as much time to let it

degass and I readily admit that I’ve never used something like an OMOO 25 from

Smooth On that only has a 15 minute potlife and a 75-minute cure time (as

opposed to Cast-A-Mold 25T, which has a one hour potlife and a 16 hour cure

time), though I’d imagine it has a considerably lower viscosity and probably

doesn’t require quite as much time to degass. In fact, the Smooth-On website

claims that vacuum degassing OMOO 25 isn’t necessary, but I’m highly skeptical

of any silicone that makes those kinds of claims (especially if pressure

casting is involved).

Here’s a pic of the silicone in the vacuum chamber with all

the air bubbles having been brought to the top and popped while under

vacuum, leaving a beautiful, smooth surface.

Once the surface of the silicone looks smooth and

bubble-free, turn the blue outlet valve to the OPEN position and allow the

vacuum to bleed off. When the gauge reaches zero, you should now be able to

remove the lid and the container of silicone.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any pictures of me actually

pouring the silicone into the mold, but the only real trick to that is to

choose one corner of the mold to pour in the silicone and let the mold fill

from the bottom up. Avoid pouring silicone directly onto the master. Also, to

prevent introducing any new air bubbles into the mold, try to pour from on high

so that the silicone pours downward in a long, thin stream.

Also, a brief word about pre-filling holes and sockets on

master parts that have holes and sockets in them (like those action figure arms

from earlier). Sometimes I pre-fill these, sometimes I don’t. Last time, like

what’s pictured below, I got a little paranoid about the silicone maybe not

filling in the sockets in the arms all the way though the more I think about

it, my fear might have been unfounded. This silicone in particular can get

between tiny gaps in Lego bricks, leaving being mini silicone

bricks-within-a-brick so why I was so paranoid about it not filling in a socket

of that size, I have no idea. But I prefilled them anyway and the molds came

out pretty good. I didn’t pre-fill any of the sockets for the example parts

(the two feet holes at the bottom of the legs and the socket at the base of the

torso that attaches the legs) and those also came out well.

So I guess it’s up to you whether you want to pre-fill holes

or not. Again, this probably depends on the quality of silicone you’re using.

If you’re using some low-viscosity Let’s Resin brand stuff you got in an Amazon

daily deals sale, it’s better to be safe than sorry and you should take all the

precautions you can.

Allow the silicone to fully cure (for me, it was 16 hours per

the cure time for Cast-A-Mold 25T) and then get ready to cut the mold (thus

giving the cut mold its namesake). Starting from the top of the mold, remove

the funnel first since it should easily snap off. Then, while slightly

stretching the mold between your fingers, make the first incision with a hobby

knife starting from the side of where the funnel used to be and make a slight

zig-zag or serpentine cut until you reach the air vent. Note that the zig-zag

cut doesn’t have to be as severe as the ones you commonly see people make in

youtube videos. Think of it more as a jagged line. Make sure it’s all one cut and

in the same direction, not multiple cuts in different directions. Then do the

same on the other side of the funnel.

Go slow and don’t cut towards you or your hands/fingers.

Observe basic knife safety here because hobby knives are just as sharp, if not

sharper, than anything in your kitchen. Cut all the way down through the

silicone (don’t tear it), until you reach the master. Try not to nick or cut

the master during the de-molding process if it’s something you care about.

.jpg)

Then, on one side of the mold, cut along the air vent in the

same jagged line pattern and repeat on the other side of the mold. It’s

important to note here that you should only cut down far enough to free the

master from the cut mold. Don’t cut the mold completely in two because that

defeats the purpose of a one-part mold. Leave it in one piece.

You know that you did a good job of cutting the mold when

you press it back together and the cut line is almost invisible.

.jpg)

I did the same thing for the cylindrical shaped mold that I

did for the legs.

.jpg)

Now, before you pour in resin (or wax or soap or liquefied Monster

Clay or melted chocolate, if you’re using a food safe silicone), you’re going

to want to get something to hold the molds together. Apply rubber bands or tape

or a combination of the two to keep the mold from parting and any casting

material from leaking out. Ensure the rubber bands or tape isn’t applied too

tightly (just enough to keep the two halves together) and that the bands or

tape is concentrating a disproportionate amount of pressure in one area of the

mold. You want even pressure all around the mold, as this will help cut down on

flashing. Flashing is the excess material left over after casting, but I’ll

cover that more when I do an article about resin casting.

When you go to cast, resin goes into the sprue hole where

the funnel used to be and resin goes out of the vent holes (as any trapped air

along with it) when the mold is adequate filled. But that’s a process for

another day. For now, rejoice in your newly created one-part cut molds. To

further extend the life of a silicone mold, either spray the inside with

silicone mold conditioner before storing it or brush the inside with a very

thin coat of Specialty Resin and Chemical brand silicone thinner (which doubles

as a conditioner that preserves finished silicone molds).

And that’s about it for one-part cut molds, at least as far as it concerns what I do. Stay tuned for future How I Do It articles, where I’ll dive into the actual process of resin casting as well as other types of molds. As always, thanks for reading and I hope this article was some help to someone out there.

Comments

Post a Comment